WHY EARLY-CAREER PROFESSIONALS FEEL IT MOST, AND HOW INSTITUTIONS CAN CLOSE IT

By Heather Smith

Gen Z is the most digitally native generation in the workforce, so why are they reporting the lowest confidence about AI at work? A recent LinkedIn News article reports that Gen Z is the least likely to believe AI will help them grow their careers or make them more efficient at work, and they are the least likely to feel supported in learning AI. LinkedIn also reports that Gen Z shows the lowest confidence in their ability to land or hold a role, dipping into negative territory on a -100 to +100 scale.

The generational headline is interesting, but the deeper story is more actionable. If Gen Z feels less confident about AI than their grandparents, it reflects the environment they are entering: rapid economic shifts and rapidly changing tools, with limited structured support.

AI IS MOVING FAST. SUPPORT ISN’T.

AI is accelerating change in tasks and roles while many organizations and institutions are still building clear learning pathways. The result is significant skill gaps.

The World Economic Forum Future of Jobs Report 2025 puts the scale of this challenge in context: employers expect 39% of workers’ core skills to change by 2030, and if the workforce were 100 people, 59 would need training by 2030. Skill gaps are identified as a top barrier to business transformation, with 63% of employers citing them as a major constraint.

Without clear learning paths, individuals are trying to leap the gap on their own. The LinkedIn News article reports only 45% of employees feel supported in learning AI skills, even as 54% plan to teach themselves in the next six months. That mismatch suggests many professionals are learning through improvised methods such as tutorials and after-hours experimentation rather than through structured guidance.

A Walton Family Foundation and Gallup report echoes the same theme for Gen Z: they are using AI, but many feel anxious and unprepared because they lack clear guidance in school and at work.

Taken together, these findings point to a system issue: adoption is accelerating faster than support structures.

WHY EARLY-CAREER PROFESSIONALS FEEL THE GAP MORE DEEPLY

The support gap show up at every career stage, but it carries higher stakes for early-career professionals.

Early-career professionals are trying to establish themselves while both the labor market and the tools of work are shifting quickly. When you are new, you often have fewer internal networks, less role clarity, and fewer reference points for how disruption eventually settles. In that context, learning AI without support can feel less energizing and more like high-stakes guesswork.

When the supports are missing, the option to pause, reskill, and reenter feels less available, especially for those without savings, flexibility, or employer backing. This is fundamentally a design challenge.

A GEN X PERSPECTIVE ON DISRUPTION AND RECOVERY

My own career path helps explain why I react strongly to this data.

I graduated high school in 1990 and began working while the early 1990s recession shaped the job market. I later started college as a nontraditional student, spending time in retail work along the way, and ultimately earned dual mechanical and electrical engineering degrees in 2001. That timing matters: I entered the engineering workforce in 2001, right as the dot-com bubble burst. The disruption was real, and it shaped early career decisions. My employer froze wages to avoid layoffs, and I stayed at an entry-level salary longer than expected, even as my responsibilities grew through promotions.

But there was also a crucial difference compared to today’s early-career environment: the entry pathways still existed, and the disruption was largely cyclical rather than existential for the on-ramp itself. Engineering work continued to expand as digital tools, automation, and globalization reshaped how we worked.

Later, after the Great Recession, I made a deliberate decision to step out and reskill through an engineering management master’s degree, essentially an MBA for engineers. That reset gave me a structured way to reenter with stronger market alignment and a clearer trajectory.

When I look at early-career professionals today, I see the challenge and I know that support is the key.

CONFIDENCE IS THE SYMPTOM. SUPPORT IS THE LEVER.

Support structures are critical for success. The Walton Family Foundation and Gallup report students who say their schools allow AI use are 25% more likely to feel prepared to use the technology after graduation, reinforcing that structure and permission matter.

Students who say their schools allow AI use are 25% more likely to feel prepared to use the technology after graduation.

Support structures matter at every stage, not just in school. LinkedIn’s AI Confidence Survey shows that only 45% of employees feel supported in gaining AI skills and knowledge, even as AI adoption accelerates across workplaces. Many workers are already taking initiative on their own: 78% are bringing their own AI tools to work, experimenting and self-teaching in the absence of formal support. Similarly, 84% of employees say they want more AI training, reflecting both enthusiasm and a gap in structured guidance. When organizations provide consistent tools, clear expectations, and opportunities to practice, employees, like students, report greater readiness and confidence.

Given proper support, people are prepared to successfully leverage AI for impact. The Walton and Gallup findings reinforce that structured environments measurably increase perceived readiness.

WHAT IT TAKES TO CLOSE THE SUPPORT GAP

Closing the support gap requires more than inspiration and access to tools. It requires a structured ecosystem that makes learning safe, practical, and career relevant.

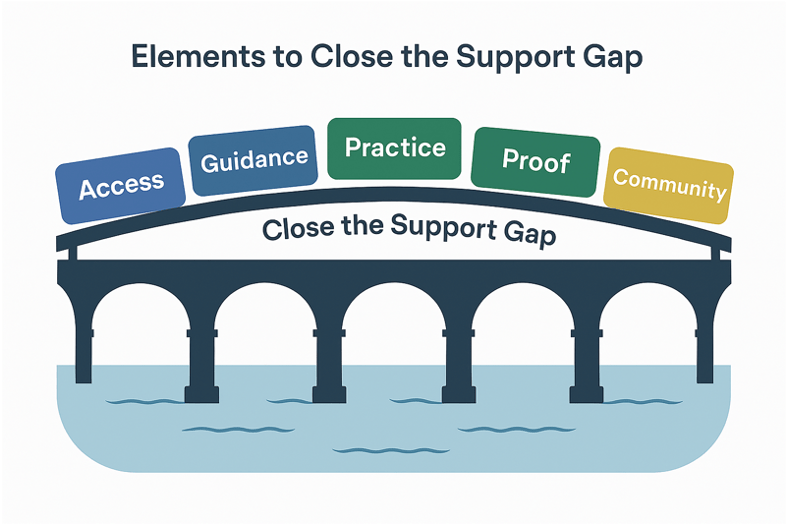

Here is a five-part framework that translates well for AI learning across higher education and industry:

- Access: Equitable, secure access to trustworthy AI tools and environments, with clear rules for privacy, data handling, and when AI should and should not be used.

- Guidance: Practical norms for appropriate use, including verification expectations and role-specific use cases.

- Practice: Repeated, low-risk opportunities to apply AI to real tasks, not just demos or theory.

- Proof: Ways to demonstrate capability and progression, including portfolios, project artifacts, and competency-based signals that learning pays off.

- Community: Social learning that normalizes experimentation across career stages and generations, turning AI adoption into shared practice rather than isolated effort.

None of these elements works well in isolation. Access without guidance can lead to uneven practices and lower trust. Practice without proof can feel like busywork. Proof without community can become performative rather than developmental. The goal is to build a bridge across the gap using a connected set of supports.

This is also where universities and professional education can play a unique role. When learners have supported access to tools, structured opportunities to practice, and communities that encourage responsible use, confidence tends to rise because competence rises.

This is also where universities and professional education can play a unique role. When learners have supported access to tools, structured opportunities to practice, and communities that encourage responsible use, confidence tends to rise because competence rises.

A SHARED CALL TO ACTION

Closing the support gap is shared work.

For employers: treat AI learning, and continuous learning more broadly, as part of work, not as something done only after hours. LinkedIn’s data suggests many are currently learning on their own, which increases uneven adoption and risk. WEF projects that 59% of the workforce will need training by 2030. At this scale, it cannot be ad hoc or left to individual initiative.

For educators: design learning that combines tool access, guided practice, evaluation skills, and ethical reasoning, because tools will change but the ability to think critically and communicate clearly remains durable. WEF highlights that analytical thinking remains the most sought-after core skill, and that resilience, flexibility, and agility are rising in importance as work evolves.

For professionals, especially early-careers: do not interpret uncertainty as personal failure. Your environment is genuinely complex. Focus on transferable practices: framing problems well, validating outputs, protecting data, and communicating decisions. And seek communities of practice, because learning together is faster and safer than learning alone.

CLOSING

This is not an AI confidence gap. It is a support gap. And we can close it.

Gen Z may feel less confident than their grandparents today, but that isn’t a permanent state; it is a symptom of a rapidly changing landscape that demands we move beyond interesting statistics toward real, structured solutions.

This is not an AI confidence gap. It is a support gap. And we can close it.

SOURCES AND REFERENCES

- LinkedIn News: Why Gen Z is less confident in AI than their grandparents, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-gen-z-less-confident-ai-than-grandparents-linkedin-news-9jeke/

- Walton Family Foundation: Gen Z Is Using AI, But Reports Gaps in School and Workplace Support, https://www.waltonfamilyfoundation.org/about-us/newsroom/gen-z-is-using-ai-but-reports-gaps-in-school-and-workplace-support

- World Economic Forum: The Future of Jobs Report 2025, https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-jobs-report-2025/

Disclosure: I used Microsoft Copilot as a writing assistant to brainstorm themes, refine the structure, and edit drafts. All claims and interpretations are my own, and I verified cited statistics and sources before publication.